Earlier this month, I returned from what I can only describe as one of the most special (travel) experiences of my life. For two weeks, I had the incredible opportunity to volunteer on Easter Island, or as it’s known by its native name, Rapa Nui (which I will stick to here). This trip was not just about sightseeing; it was a proper deep dive into understanding how this remote island in the middle of the Pacific confronts its pressing climate-related challenges. This experience holds an extra special place in my heart, not just because I had the opportunity to get hands-on with a project that means so much to me, but also because it was an absolute childhood dream come true! *happy sobs 🥹*

Rapa Nui, with its volcanic terrain, holds a narrative of resilience and adaptation. Yet, in recent years, this remote paradise has been facing some serious issues brought on by climate change. From relentless winds and scorching heat to droughts and extreme weather events, the island is already dealing with urgent environmental crises. Approximately 95% of its surface bears the brunt of these impacts, necessitating immediate action to combat threats like drought, erosion, and wildfire against its delicate ecosystem. In 2022 alone, there were 13 consecutive dry years, marking the driest period since 1967. And to top it off, more than half of the island’s soils are highly erodible, with fires only making matters worse by causing desertification and erosion.

My fascination with Rapa Nui dates way back to my early days, but it took on a new sense of urgency in October 2022 when wildfires ravaged over 100 hectares of its land. Much to my surprise, it was just googling for volunteering opportunities in South America that I stumbled upon what felt like hitting the jackpot – a chance to contribute to Rapa Nui’s conservation efforts within CONAF, Chile’s impressively comprehensive forestry framework.

There is so much I want to share about this trip, the island and my overall experience that this entry is broken down into the following sections:

- SUPER Brief History of Rapa Nui

- CONAF (Chile’s National Forest Corporation)

- The Volunteering Experience

- Rapa Nui’s Eco- and Social Crises

- Island Life

- Super *SUPER* Brief History of Rapa Nui

Rapa Nui (Isla de Pascua in Spanish), a Chilean territory, was named Easter Island by the Dutch explorer Jacob Roggeveen upon his discovery of the island – you guessed it – on Easter Day in 1722. This tiny volcanic gem, nestled in the vast South Seas, remains the most isolated inhabited place on the planet, lying nearly 3,700km (2,330mi) off the coast of South America—a five-hour flight from Santiago. Other nearby neighbours include Pitcairn – 2,075km (1,289mi) to the east, and Tahiti, the largest island of French Polynesia, 4,250km (1,990m) to the northeast.

Formed by three volcanoes arranged in a triangular shape, Rapa Nui is roughly the same size as Monaco or Manhattan. Today, the island is home to just over 7,000 people (2,000 of whom are descendants of the Rapa Nui people) residing primarily in the only village of Hanga Roa. The Rapa Nui National Park, a protected Chilean wildlife area and, since 1995, UNESCO World Heritage Site, makes up nearly half of the island’s territory.

The island’s history is puzzling and complex, shaped by the Polynesian settlers who arrived centuries ago. Renowned for its archaeological sites, this dot in the ocean is usually recognised by the monumental statues known as moai. The early inhabitants cultivated the land sustainably, relying on natural resources while respecting the island’s fragile ecosystem (more on that later). Though estimates vary, it’s generally believed that at its peak, Rapa Nui had a population of several thousand people – quite possibly reaching 20,000 at some point – but limited archaeological evidence and uncertainties surrounding the island’s carrying capacity and environmental dynamics currently do not offer more insight than that.

The sight of towering stone figures, looking godlike and humanly primal at the same time, must have left early visitors in disbelief. To them, the idea that such immense sculptures could be created by the inhabitants of this small, isolated island seemed impossible, as James Cook remarked in 1774: “We could hardly conceive how these islanders, wholly unacquainted with any mechanical power, could raise such stupendous figures.”

Allegedly until 15th century, the Rapa Nui people meticulously carved the statues, which held profound significance in their religious and social practices, symbolising their deep connection to the spiritual realm. Each moai represented an incredible feat of labour, with some transported across the island, showcasing the community’s advanced engineering and logistical skills.

For at least several centuries, Rapa Nui society flourished, developing sophisticated agricultural techniques to support its expanding population. However, environmental degradation, coupled with societal shifts and potential conflicts, led to a gradual decline in both population and cultural vibrancy by the 18th century. The arrival of Europeans marked a point of no return: contact with outsiders brought diseases that devastated the local population, introduced new social dynamics and cultural disruptions, eroding traditional beliefs and practices that had long defined Rapa Nui identity.

The island’s history over the past century has been turbulent. Chilean authorities gained control over Rapa Nui in 1888 and imposed harsh restrictions on the indigenous population, confining them to controlled areas and restricting their movements. Efforts to address these inequalities were hindered by the repressive political climate in Chile, particularly during the 1960s. Through continued agitation and petitions, Rapa Nui gained more control over its governance, with the installation of the first Rapa Nui governor in 1984 and the establishment of enduring democratic institutions by 1992.

- Chile’s National Forest Corporation (CONAF)

Disclosure note: Prior to my volunteer experience, I was not familiar with CONAF

Established in 1973, CONAF, or the National Forestry Corporation of Chile, stands as a key governmental organisation entrusted with the management and preservation of Chile’s diverse forests, biodiversity, and protected areas. Amidst Chile’s varied ecosystems – from the arid Atacama Desert to lush temperate rainforests – CONAF’s mandate encompasses safeguarding the nation’s natural resources while fostering sustainable development.

Chile boasts incredibly diverse ecosystems, from the Atacama Desert to temperate rainforests; the forest coverage, as of 2021, represents almost a quarter of the national territory. CONAF works to conserve the rich biodiversity found in the country’s forests and protected areas: this includes monitoring endangered species, habitat restoration, and implementing conservation programs. Unfortunately, given Chile’s susceptibility to wildfires (specially during dry seasons), CONAF also plays a crucial role in fire prevention efforts, including education, early detection systems, and coordinated firefighting responses during fire seasons.

The enactment of the Native Forest Recovery and Forest Promotion Law in 2007 (which took 15!!! years to pass) underscored Chile’s commitment to sustainable development practices, positioning the country as a leader in environmental stewardship within Latin America. Living up to the spirit of this legislation, CONAF strives to foster social and economic progress for rural communities across the country while maintaining a delicate balance with environmental conservation efforts.

Now let’s turn to the organisation’s island branch. Here, the vulnerability of Rapa Nui to the effects of climate change presents a unique set of challenges. Prolonged droughts, rampant erosion, and devastating wildfires threaten the island’s environmental integrity, posing significant challenges to its delicate ecosystem. In response, CONAF launched the “Climate Change Programme in Rapa Nui” in 2018, a multifaceted initiative aimed at climate change adaptation.

At the heart of this programme lies a robust strategy encompassing substantial reforestation efforts and community-driven adaptation activities. Through education, training, and communication campaigns, CONAF seeks to enable local communities to combat the adverse impacts of climate change effectively. On a short-term front, CONAF aims to plant 120,000 trees in high-erosion sectors by the end of 2024, with plans for further activities designed to support Rapa Nui’s ongoing adaptation efforts -> which is where I step in! 🌱

- The Volunteering Experience

My office on the island was slightly different from the one I have in Amsterdam – it was CONAF’s local nursery (vivero in Spanish) for plants! Nurseries play a critical role in nurturing plants during their early stages, providing the ideal conditions for growth. These facilities are designed to meet the specific needs of plants, offering controlled environments that foster healthy germination, root development, and overall vitality.

Daily tasks varied depending on the day, the weather, and any ad hoc needs. Many hours were spent in the bag filling area, located near the substrate collection and screening area, which is crucial for preparing the necessary substrate to fill bags where larger plants will be planted after germination. The substrate, tailored to different plant species, typically blends soil, perlite (amorphous volcanic glass), and specialised fertilisers. Solarisation further treated some substrates, reducing pathogens and ensuring optimal growth conditions.

The first couple of days, our efforts centred on sowing seeds, particularly of aito and albicias trees (left picture; pictured right are me and Mata, transferring 200 baby mandarin sprouts to their new bigger homes), renowned for their rapid growth rates. These adaptable species thrive across various temperature ranges, developing robust root systems crucial for soil stability. By planting them later on, we fortify our soil defences with their resilience.

Within the vivero, plants are given ample space to flourish without competition from neighbouring species, fostering the development of strong root systems and lush foliage. As plants matured, they are either transplanted into larger containers or prepared for outdoor planting.

One particularly interesting feature, which I first saw at the vivero but ultimately common all over Rapa Nui, is called manavai (pictured above). A great example of ingenuity and adaptation to environmental challenges, manavai are rock gardens, enclosed spaces with circular stone walls. These structures serve multiple functions: they retain moisture in the soil, regulate soil temperature, prevent erosion, and even act as slow-release fertilisers. At some point in Rapa Nui’s history, they helped to maintain the productivity of plants essential for food, art, construction and ceremonies.

I also spent a bit of time getting to know the plants growing around the nursery. For example, it was my first time ever seeing the curcuma (turmeric) flower (on the left) — who knew it would be this cute? I also discovered the noni plant (in the middle), a weird-looking fruit that has traditionally been used for medical treatments by the Rapa Nui people – different parts of the plant would treat ailments such as infections, skin conditions and digestive issues, whereas leaves could be used for making dyes and noni wood – for crafting tools and utensils.

The current native flora of Rapa Nui has approximately 48 species, 11 of which are endemic. What struck me as particularly fascinating was the potential explanation of the presence of crops such as inga edulis, sometimes referred to as the ice-cream bean tree (picture on the left), originally native to South America. It’s plausible that such crops found their way to the island through early human migrations long before European contact in the 18th century. Polynesian settlers, possibly present on Rapa Nui well before 800 A.D., were adept navigators capable of undertaking loooong trips across the Pacific, thus facilitating potential interactions with South American cultures.

The everyday life at the vivero was also a good fun, with friendly shenanigans in the kitchen (something that all offices clearly have in common 😁) and all around.

In honour of World Water Day, me and two other volunteers joined a field trip alongside third-year tourism students. Our destination was the crater Rano Aroi, a vital source of fresh water for Hanga Roa. Beyond just observing the mechanics of the island’s water systems, the journey turned into an enjoyable hike around the youngest volcano, Terevaka.

Throughout the trek, we paused at various points to get into discussions about Rapa Nui’s native flora, the environmental hurdles it faces, past archaeological explorations in the vicinity, and the significance of maintaining a strong connection with nature. It was during one of these moments that we embraced the concept of tree-hugging, a simple yet beautiful gesture (love me a good tree hug 🌲).

The kids were so nice and friendly as well! 💖

One highlight of my time on the island was joining the first *big* reforestation event of 2024, where 1,000 new trees were planted on the slopes of the volcano Poike. The volcano is severely affected by erosion (just look at how orange it is! my head could practically blend in there), with large areas completely lacking soil, with gullies of up to 4 meters and, in addition, it is exposed to the relentless north wind and the impact of grazing animals, presented a formidable challenge.

Here’s a short clip from the event, in case you’re curious:

As we all know, trees stand as the backbone of biodiversity, providing clean air, regulating climate, and offering crucial protection for the delicate soils and aquifers of islands like Rapa Nui. Planting trees emerges as one of the most effective and economical strategies to counteract the impacts of climate change. Yet, particularly in places like Rapa Nui, these forests will serve as essential guardians against soil erosion, enhance water retention for the groundwater sustaining local communities, and act as barriers against the island’s prevalent strong winds, among a multitude of other advantages.

Over nearly two decades of systematic effort, CONAF has carefully researched and nurtured species within the vivero, handpicking those best suited to thrive in these harsh conditions. Among them are ceibo trees, acting as windbreaks to shield interior plants, albicia falcata and lebec trees, providing ample shade, and purau trees, specialists in controlling erosion in gullies.

Similar plantation events take place several times a year.

On my final day, the vivero hosted a tour and a tree planting workshop for students, some of whom I had met during our earlier field trip. Alongside the firefighters stationed adjacent to the nursery, they enthusiastically planted 200 trees! Amidst the planting, they delved deeper into the significance of understanding the species before planting them in the soil. As these trees adapt and grow, they manifest various characteristics: pods and seeds suitable for craftsmanship, trunks with wood quality ideal for carving, and the pivotal role of carbon absorption and nitrogen contribution in soil nourishment. Participants also explored the ecological functions, environmental adaptation, and overall impact of each plant, fostering an understanding of how to create optimal conditions for their growth.

- Rapa Nui’s Eco- and Social Crises

In 2016, UNESCO identified Rapa Nui National Park as one of the seven World Heritage Sites most vulnerable to climate change. In October 2022, devastating fires damaged numerous archaeological sites within the park, particularly affecting the Rano a Raraku volcano crater and quarry, home to over 400 moai statues of significant cultural and spiritual value. Responding to this crisis, UNESCO, in collaboration with local and national stakeholders, secured funds to assess the damage and develop a comprehensive disaster preparedness plan.

Unfortunately, this is far from the island’s first environmental crisis. In popular literature, Rapa Nui has emerged as the epitome of prehistoric human-induced environmental catastrophe and cultural collapse. A *prevalent* (but not necessarily most accurate) narrative today depicts an obsession of the ancient islanders’ with the moai as the primary catalyst for its ecological ruin. Many scholars present this narrative as a cautionary tale, drawing parallels to our own degradation of the global environment.

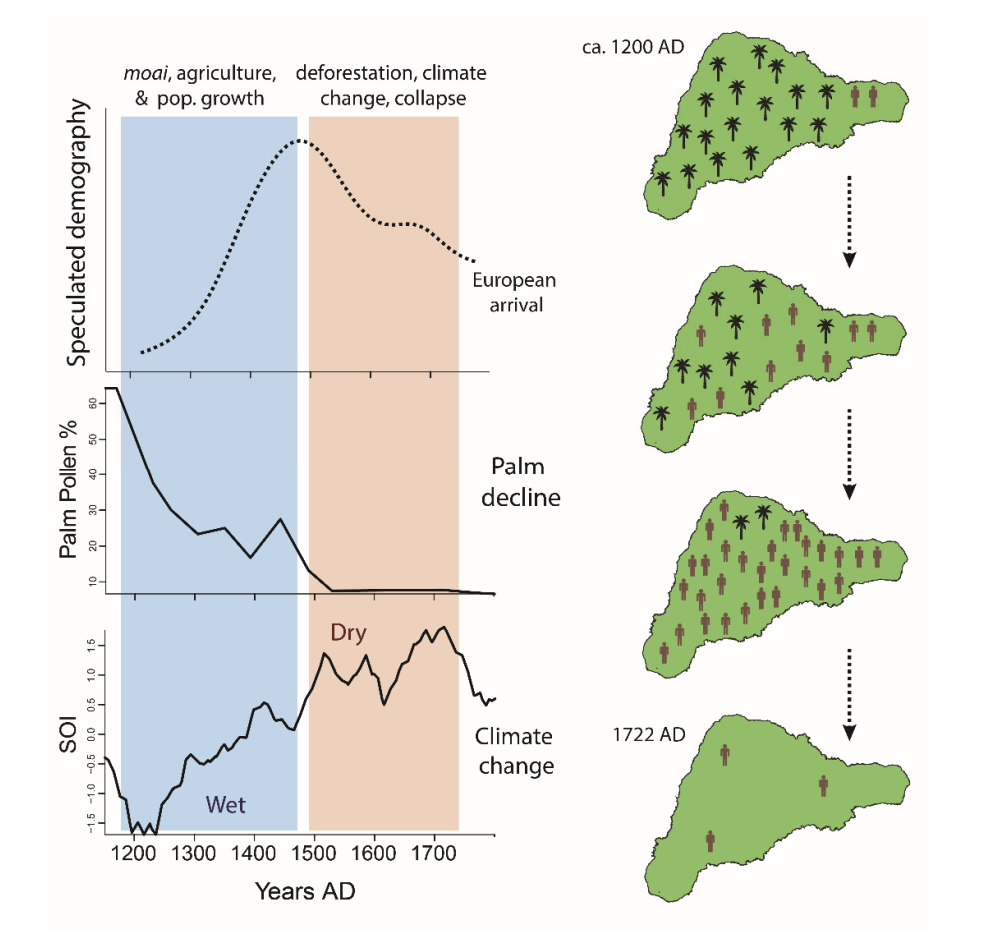

What’s the story? According to this account (popularised by Jared Diamond), Rapa Nui’s once thriving and prosperous population engaged in massive statue construction and transport, leading to over-consumption of the island’s resources and ecological catastrophe. The islanders’ demand for resources such as soil nutrients, birds, marine resources, fresh water, and timber, necessary for food and statue transport, increased dramatically over centuries. This led to deforestation, extinction of land bird species, soil erosion, loss of soil nutrients, and depletion of fresh water and fisheries (illustrated by the top graph). Eventually, resource availability could not sustain the population, *allegedly* leading to warfare, starvation, cannibalism, depopulation, and cultural collapse.

However, most recent research on Rapa Nui’s environmental history reveals a more nuanced and gradual process of deforestation than previously thought. While human activity undoubtedly played a significant role, evidence suggests that factors such as landscape burning and seed predation by invasive species like the Pacific rat also contributed. Additionally, a period of drought has been proposed as a climatic factor influencing deforestation. Recent coring studies challenge previous assumptions of abrupt and catastrophic deforestation, indicating a spatially heterogeneous and gradual process over centuries (illustrated by the bottom graph).

The loss of the palm forest on Rapa Nui undoubtedly had significant ecological implications, but its impact on human communities’ sustainability requires careful consideration. While it is commonly assumed that the loss of palm trees reduced the island’s carrying capacity, there is limited archaeological evidence supporting palms as a significant dietary source. Analyses suggest that dryland cultivation of crops, along with fishing and marine foraging, formed the primary basis of the diet. Additionally, the extinction of certain bird species likely had minimal impact due to the importance of introduced chickens in the diet.

Claims of reduced carrying capacity due to soil erosion and nutrient depletion from deforestation are also challenged by recent studies. While evidence of soil erosion exists, particularly in certain areas, island-wide studies indicate that severe erosion affects only a small percentage of the land surface, with much of it attributed to post-contact effects like historic sheep ranching.

Overall, while the loss of the palm forest had ecological consequences, its impact on human sustainability and carrying capacity may have been less significant than previously assumed.

One research study from 2021, for instance, utilises Approximate Bayesian Computation (ABC) to investigate how past human populations responded to environmental and climatic changes. The study addresses deficiencies in previous paleodemographic reconstructions by proposing a method for fitting complex demographic models to observed Summed Probability Distributions (SPDs) of radiocarbon dates. Contrary to previous hypotheses, the study indicates relatively steady population growth from initial human settlement until the period following European arrival.

These findings challenge the notion of a pre-contact population collapse on Rapa Nui, suggesting instead that populations adapted to environmental changes and maintained stable communities. The study also provides insights into the effects of climate change on the island, indicating that populations adapted to climate perturbations by relying on coastal groundwater sources.

Another research, also from 2021, also highlights the resilience of Rapa Nui communities in the face of environmental challenges and argues that they devised adaptive techniques to cope with changing ecological conditions. Contrary to the assumption that selfish behaviour leads to the collapse of cooperative groups, Rapa Nui communities cooperatively managed common-pool resources in a sustainable manner for centuries. In this light, Rapa Nui serves as a model for long-term sustainability, as communities lived sustainably for more than five centuries before European arrival.

To conclude, I would say that most recent investigations suggest that Rapa Nui’s population remained stable and adapted to environmental challenges over the course of its occupation of the island. In turn, the narrative of a tragedy of the commons on Rapa Nui requires reevaluation given these findings, highlighting the importance of contextualising environmental changes and human responses in archaeological paleo-ecology research.

- Island Life

One of the most striking aspects of Rapa Nui was its island time, where the pace of life seemed to slow down, without slowing down the life itself. There was a distinct sensation of time not following to its usual linear path – an experience both disorienting and liberating. I have no idea how else to describe it but maybe you get the idea. 🌞

For example, instead of adjusting to local time upon connecting to a network, even phones stay fixed to Santiago’s time zone until manually adjusted… How is that for a metaphorical reminder of the need to align yourself with the island’s wavelength?

Island life, if you ask me, is a different way of being. Having previously experienced island life on another island – in Ireland – as well as remembering my travels to other parts of Polynesia, I anticipated a certain level of familiarity, yet Rapa Nui is entirely a world of its own. Perhaps it has to do with its teeny tiny population size, where everybody *does* know each other and therefore feels very safe. Here is an example: in moments of horrible weather, offers of rides from passing strangers were not uncommon – a gesture that would trigger panic elsewhere but felt entirely natural in this close community. Once, on the outskirts of Hanga Roa, where a pack of stray dogs – hungry-looking yet probably harmless – began trailing me, causing quite a bit of unease. Within moments, a local resident appeared, and sensing my concern he took me by my hand and walked me to the main road.

Reflecting on my time there, the two weeks and a day felt more akin to a month of my usual European routine, where schedules are often packed to the brim. I found myself embracing – or trying to, at least – a simpler way of life that prioritised presence over productivity. Whether sharing a meal, saluting to the sunset, or exploring the island’s archaeological sites, even mundane moments felt a little more… real? (of course, being away from my everyday responsibilities also helped 🤭)

While still in Santiago, a friend of mine gave me a great tip to stock up on groceries – food on the island is expensive! I ended up packing several kilos of pasta, lentils, oats, jams and whatnot (pictured on the left; all of that cost about CPL 36,000) – as all these things need to be imported from the mainland, prices multiply easily. But, of course, I still treated myself to a meal out here and there – with ceviche being the absolute favourite.

Speaking of things being brought from/to the continent, one of my main concerns was waste, especially plastic. In an effort to minimise my footprint, I opted for as many solid toiletries as possible, reducing the amount of single-use plastic items in my backpack (some of which I discussed in this entry). For the rest, I collected all packaging and disposed items to take back with me to Santiago, but I was curious to learn how it generally works on Rapa Nui.

Fortunately, CONAF is not alone in addressing the sustainability challenges facing Rapa Nui. Shortly after my departure, the Pacific Leaders Summit convened in Hanga Roa to confront the urgent issue of plastic and microplastic pollution in the Pacific. Rapa Nui itself is facing a severe crisis of plastic pollution, with its only proper beach, Anakena, being heavily affected by the presence of microplastics: about 4.4 million pieces of trash wash up annually, Despite not being the primary source of this waste, Rapa Nui is on the receiving end due to its geographical location within the South Pacific Gyre, which facilitates the accumulation of floating ocean plastics.

Efforts to manage and mitigate plastic waste on Rapa Nui include the operation of a waste facility near Hanga Roa, where plastics and cans are processed into transportable bales. During the two years of the pandemic, the island collected 11 tons of garbage. Latam Airlines also has committed to transport 300 tons of waste to the mainland therefore assisting in the island’s waste management efforts.

As a final note, I want to share a personal anecdote. For a while now, I had been thinking of getting a tattoo, and as soon as I arrived on the island I knew this would be the right place to get it (I did not have any before, knowing full well the challenge of resisting the urge to stop at just one). Throughout my stay on Rapa Nui, I was looking around to get inspiration and find something that would just click, and – voila! – one of the moai really spoke to me (no, it is not the one on the right).

But the connection didn’t end there. From the moment I left Rapa Nui, it has been following me everywhere. Whether it is encountering doppelgängers of the people I met on the island, stumbling upon uncanny references, or dreaming about the island night after night, it is like the island is still talking to me.

When I shared this observation with a friend, she chuckled, “You’ve got a moai on YOUR LEG! Of course you’ll always have one foot there, what did you expect!”… It seems she may be onto something after all.

***

Ain’t gonna lie, my memories of the island are still much very rose-tinted — it is not every day that your childhood dream comes true! Rapa Nui has definitely kept a piece of my heart (or the other way around?) and something tells me this will not be my only visit. And so, I say maururu, ioarana & until next time! 🤍❤️🤍

Leave a comment