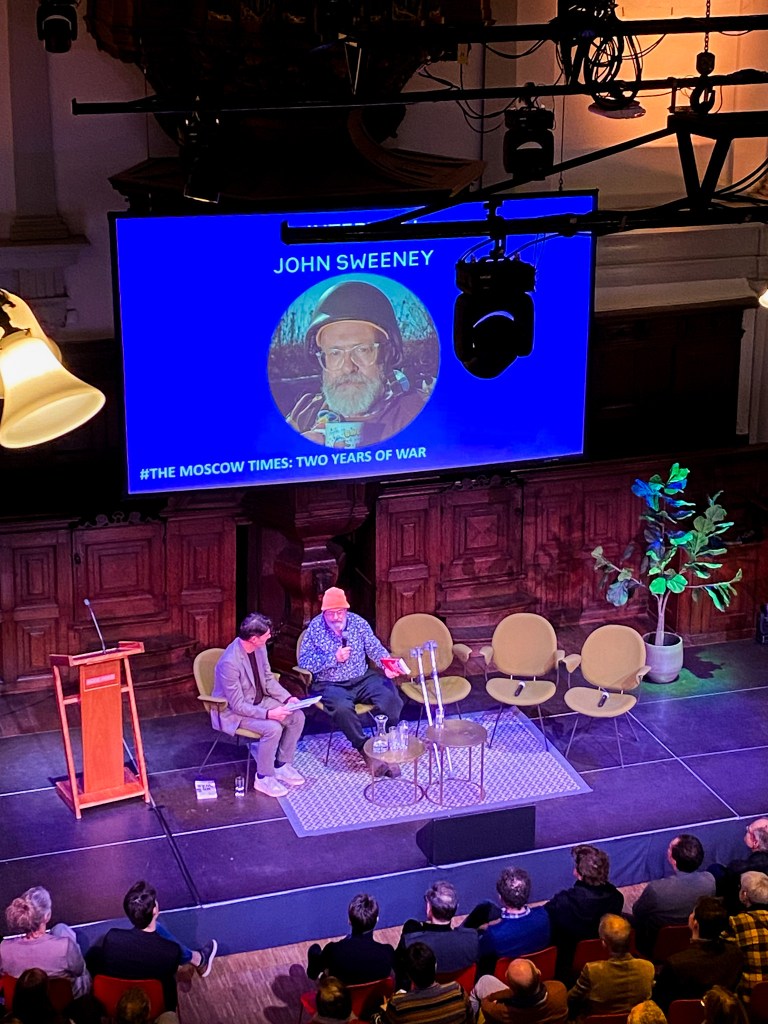

This evening, I ended up at an event that stirred today’s entry in a direction that I could not see coming at all. By chance (and very last minute), I found out about a panel organised by the Moscow Times, an independent English-language and Russian-language online newspaper founded by the Dutch media magnate Derk Sauer in 1992. As this month marks two years of the war in Ukraine, guests were invited to reflect on the future of Russian journalism in exile and journalism in general during these crazy times.

Amsterdam, together with Tbilisi, Riga and Berlin (and other cities), have recently become home to several journalists fleeing Russia at the risk of being prosecuted. In case you did not know, on March 14, 2022, Russia’s parliament passed a law imposing a jail term between 7 and 15 years for intentionally spreading misinformation about the military. (guess what min sentence one can get for a murder? 6 years) In other words, being an independent journalist in Russia currently means facing very tangible risks of getting jailed, fined, and forced out of the country for telling the truth.

Among the speakers was Marina Ovsyannikova (pictured left), former editor of Russia’s state-run Channel One, rose to ‘fame’ in March 2022 when she interrupted a live broadcast of a state television news programme to protest the war in Ukraine (nobody else followed suit). Receiving humanitarian protection from the French state allowed her to relocate to Paris with her daughter, but she is separated from her son and mother, who are still living in Moscow. Back in Russia, she has been sentenced to 8.5 years imprisonment.

Another speaker was Mikhail Fishman, the anchor of the independent TV channel TV Rain and one of the journalists I have been following for many years. One of the few independent TV channels in Russia, TV Rain had been smoked out of the country and found brief refuges in Georgia and Latvia prior to its broadcasting license in the Netherlands. I cannot thank this channel enough for its tireless work over the years, providing such an incredible coverage of news back home and beyond.

With discussions spanning from the colossal impact of propaganda and its ability to shape narratives and influence minds on a grand scale to the art of keeping hope for the best (the emergence of anti-war sentiment provides some glimmer of hope?), it’s been quite the moving journey.

The experience of social disconnectedness and perceived isolation, combined with fear, underscores the challenges of maintaining a sense of connectedness and empathy in a world bombarded with information. Compassion fatigue is a real concern, which emphasises the need for self-care and strategic engagement to avoid emotional burnout while staying informed and involved.

The year ahead is filled with uncertainties. The upcoming presidential elections in Russia and the US is a call to collective reflection, engagement, and action, recognising that, despite the complexities, individuals can contribute to shaping a better future through informed, and purposeful efforts. You can’t do much from jail, so let’s use our freedom meaningfully.

If you’re interested, you can watch the whole event on YouTube.

***

In order to not leave this post on a grim note, so I would like to share the following – slightly modified – repost from my old travel blog on why Russians do not smile (told ya, not grim!). After all, creating a positive impact on the world requires a certain level of understanding of each other’s differences, doesn’t it?

***

November 25, 2015

The other day, I had a conversation with a friend who had recently returned from Russia. It’s always fascinating to hear about foreigners’ experiences in your own country, isn’t it? Given Russia’s reputation, I was a bit apprehensive about what my friend might share. Fortunately, he had a great time, despite encountering a few minor setbacks. As I breathed a sigh of relief, my friend posed a question: “Why do people in Russia never smile at each other?” This query is one I’ve encountered numerous times during my years abroad, and I always have a ready response.

The perceived lack of smiles among Russians, often mistaken for sullenness, is a common notion. While some may consider it a stereotype, from a Western perspective, it’s a valid observation. Casual smiles from passers-by are rare, more common in the service industry and certain institutions, but generally, maintaining a neutral expression is the norm. Foreign tourists often comment on this, prompting my standard explanation: “We smile when we mean it.” Unlike many other cultures, politeness in Russia doesn’t necessarily involve smiling. It’s a cultural difference where a smile carries significant meaning and isn’t used randomly or superficially.

My friend, however, remained unconvinced: “How can people find smiles rude or offensive?” It’s a fair question, considering that a smile is universally viewed as an expression of positive emotions. I explained that in Russia, sincerity is highly valued, and a smile conveys genuine feelings, ranging from acknowledgment to intimacy. Reciprocating with a smile isn’t guaranteed; instead, it’s an invitation to initiate contact. A ‘polite’ smile is considered insincere, fostering a sense of distrust. In this society, smiling at a stranger can be interpreted as romantic interest or, at worst, invasion of personal space. A Russian smile isn’t casual; it’s informative and requires a genuine foundation.

It’s essential to emphasise that this social construct isn’t merely an unspoken rule acquired over time; it’s deeply ingrained in folklore and instilled from an early age. Even proverbs caution against joking and laughter: for instance, joking around leads to trouble and that those laughing for no apparent reason are fools. These expressions are not archaic, although you are more likely to hear them from older people. This trait extends beyond everyday interactions and influences professional settings, such as immigration officers at arrivals not wearing smiles.

Reflecting on this , I came across the video above of Jake Gyllenhaal discussing the topic on the Late Show with David Letterman. To Americans, the practice of non-smiling in Russia is as perplexing as the Russian practice of saying “How are you?” in passing is to them. These differences in smiling behaviours go beyond social etiquette and should be examined in a broader cultural context.

While historically, Americans have shifted towards direct manipulation of emotions1, Russians celebrate open expression of emotions2, considering it a sign of being alive. If you’ve ever dabbled in the works of Dostoevsky or Nabokov, you’d find yourself swirling in a whirlpool of emotions—sometimes, it feels like you need a lifeline to get out of those existential waters.

Take Dostoevsky, for example. He’s like the maestro of misery, painting vivid pictures of suffering and despair in his characters. According to our friend Fyodor, Russians have an innate need to suffer, and Russia, in essence, is a country of suffering. For suffering is a loaded term, rather than exposing yourself to pain his understanding implied thoroughly living through things, pouring your heart into them, and deeply caring.

Partly based on Dostoevsky’s fictional personalities, Freud outlined an analogy comparing literary trends in national groups with neurotic behaviour of individuals. “Even those Russians who are not neurotics are deeply ambivalent”, he wrote in a letter to Zweig. Through the prism of Dostoevsky (an epileptic suffering from severe attacks) and his works such as Brothers Karamazov, Freud analysed Russia as a country of melancholic, nihilistic, and sexually repressive people. His notion of the Russian ambivalence included a destructive or self-destructive instinct mixed with creativity, a poor sense of self, combined with a need for a powerful authority figure in control. Judging by Freud’s observations, it is quite impressive Russians are still alive (are we???).

Then there’s Nabokov, chiming in with his notion of toska—a Russian word that encapsulates this whole spectrum of soul-crushing feelings. You ever get those days (yes, plural) where you just feel this deep ache in your soul for… well, something? That’s toska for you!

This term describes a quintessentially Russian state of mind: “No single word in English renders all the shades of toska. At its deepest and most painful, it is a sensation of great spiritual anguish, often without any specific cause. At less morbid levels it is a dull ache of the soul, a longing with nothing to long for, a sick pining, a vague restlessness, mental throes, yearning. In particular cases it may be the desire for somebody of something specific, nostalgia, love-sickness. At the lowest level it grades into ennui, boredom.” 34(love this for us)

Some authors spoke of how spiritual geography corresponds with physical: the immensity of the land translates into a “predilection for the infinite” in the Russian soul. Perhaps this is why there is deep respect and appreciation for the beauty, even nobility of the concept of toska within our culture: it is an endeavour to achieve tranquillity in its own right. Russian culture has a lot of existentialism to it – something I believe Dostoevsky documented better than any other of our classics.

To sum up, one could say Russian culture embraces, if not celebrates, existentialism? Ah, what a happy bunch.

***

- Historians Carol and Peter Stearns noticed that “during the past two hundred years, Americans have shifted in their methods of controlling social behaviour toward greater reliance on direct manipulation of emotions.” Almost sounds like an extract from Brave New World, doesn’t it? If any display of all but positive emotions is frowned upon, then we have a very Huxley-esque situation indeed: “No pains have been spared to make your lives emotionally easy – to preserve you, so far as that is possible, from having emotions at all […] When the individual feels, the community reels.” ↩︎

- Anthropologist Geoffrey Gorer argued that Russians are in opposition to this approach. Taking pleasure in openly expressing the emotions as they come carries major cultural significance, as “feeling and expressing the emotions you feel is the sign that you are alive; if you don’t feel, you are to all intents and purposes dead.” Whereas behaviour described as emotional has a negative connotation in the English language, there is a considerable Russian vocabulary for the act of expressing emotions such as “pouring our one’s soul”, which is a valued part of living. ↩︎

- Linguist Anna Wierzbicka, who is famous for her outstanding work in cross-cultural linguistics, points out “different contexts may highlight different components of this complex but unitary concept”, and when used as a verb it refers to the anguish felt in response to the absence of something which is loved very much. The word defines a capacity for an expansive, articulate, and elaborate feeling of maddening ‘unsatisfiedness’, an insatiable searching, grand metaphysical anguish, while encompassing them all in one mental state. ↩︎

- Unlike sadness or apathy, toska is said to be a public, social mood. Fighting for survival was the daily reality for many Russians over the course of centuries. With the day-to-day life being very difficult for the majority of people, worry became the default look on a Russian’s face. It was particularly prominent in the years after 1905 as the writer and philosopher Dmitry Merezhkovsky described his walk around St. Petersburg in 1906 for the first time since returning from abroad: “Terrible toska on people’s faces”. Contemporary literature and newspapers of the time echoed this mix of melancholy and listlessness of the society in their works, although some perceived it as a way of broadcasting and spreading such dark moods. Writers and columnists argued: “The mirror is not to blame”. The years between 1906 and the war were also marked by an epidemic of suicides, with many felos-de-se leaving final notes; one frequently cited note read “toska, limitless toska”. So, if there is no good spirit and no material well-being, a Russian for the most part had no reason to smile. ↩︎

***

The challenges that I tackled today were vegan food (failed; I must have been feeling protein-deficient because I was craving eggs), no single-use plastic (failed as I emptied a couple of skincare bottles), compost (still going strong), unplugging devices that are not in use (did not even have to unplug them again), five-minute shower (failed), and monetary donation to a cause I care about (you might be able to guess which one).

To sum up, this is today’s progress:

| SUCCESS | FAIL |

|---|---|

| Unplug devices that are not in use | Single-use plastic (empty skincare products; a bag of nuts) |

| Compost (coffee + fruit peels) | Go paperless (printed shipping label 😪) |

| Donate to a cause that matters | Five minute shower |

| Vegan food (had a couple of eggs) |

Leave a reply to Day 10: Where Ec0-Care Meets Self-Care – Fair February Cancel reply